Knuth–Bendix completion algorithm

The Knuth–Bendix completion algorithm (named after Donald Knuth and Peter Bendix[1]) is an algorithm for transforming a set of equations (over terms) into a confluent term rewriting system. When the algorithm succeeds, it has effectively solved the word problem for the specified algebra.

An important case in computational group theory are string rewriting systems which can be used to give canonical labels to elements or cosets of a finitely presented group as products of the generators. This special case is the current focus of this article.

Contents |

Motivation in group theory

The critical pair lemma states that a term rewriting system is locally confluent (or weakly confluent) if and only if the critical pairs are convergent. Furthermore, we have Newman's lemma which states that if an (abstract) rewriting system is strongly normalizing and weakly confluent, then the rewriting system is confluent. So, if we can add rules to the term rewriting system in order to force all critical pairs to be convergent while maintaining the strong normalizing property, then this will force the resultant rewriting system to be confluent.

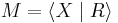

Consider a finitely presented monoid  where X is a finite set of generators and R is a set of defining relations on X. Let X* be the set of all words in X (i.e. the free monoid generated by X). Since the relations R define an equivalence relation on X*, one can consider elements of M to be the equivalence classes of X* under R. For each class {w1, w2, ... } it is desirable to choose a standard representative wk. This representative is called the canonical or normal form for each word wk in the class. If there is a computable method to determine for each wk its normal form wi then the word problem is easily solved. A confluent rewriting system allows one to do precisely this.

where X is a finite set of generators and R is a set of defining relations on X. Let X* be the set of all words in X (i.e. the free monoid generated by X). Since the relations R define an equivalence relation on X*, one can consider elements of M to be the equivalence classes of X* under R. For each class {w1, w2, ... } it is desirable to choose a standard representative wk. This representative is called the canonical or normal form for each word wk in the class. If there is a computable method to determine for each wk its normal form wi then the word problem is easily solved. A confluent rewriting system allows one to do precisely this.

Although the choice of a canonical form can theoretically be made in an arbitrary fashion this approach is generally not computable. (Consider that an equivalence relation on a language can produce an infinite number of infinite classes.) If the language is well-ordered then the order < gives a consistent method for defining minimal representatives, however computing these representatives may still not be possible. In particular, if a rewriting system is used to calculate minimal representatives then the order < should also have the property:

- A < B → XAY < XBY for all words A,B,X,Y

This property is called translation invariance. An order that is both translation-invariant and a well-order is called a reduction order.

From the presentation of the monoid it is possible to define a rewriting system given by the relations R. If A x B is in R then either A < B in which case B → A is a rule in the rewriting system, otherwise A > B and A → B. Since < is a reduction order a given word W can be reduced W > W_1 > ... > W_n where W_n is irreducible under the rewriting system. However, depending on the rules that are applied at each Wi → Wi+1 it is possible to end up with two different irreducible reductions Wn ≠ W'm of W. However, if the rewriting system given by the relations is converted to a confluent rewriting system via the Knuth–Bendix algorithm, then all reductions are guaranteed to produce the same irreducible word, namely the normal form for that word.

Description of the algorithm for finitely presented monoids

Suppose we are given a presentation  , where

, where  is a set of generators and

is a set of generators and  is a set of relations giving the rewriting system. Suppose further that we have a reduction ordering

is a set of relations giving the rewriting system. Suppose further that we have a reduction ordering  among the words generated by

among the words generated by  . For each relation

. For each relation  in

in  , suppose

, suppose  . Thus we begin with the set of reductions

. Thus we begin with the set of reductions  .

.

First, if any relation  can be reduced, replace

can be reduced, replace  and

and  with the reductions.

with the reductions.

Next, we add more reductions (that is, rewriting rules) to eliminate possible exceptions of confluence. Suppose that  and

and  , where

, where  , overlap. That is, either the prefix of

, overlap. That is, either the prefix of  equals the suffix of

equals the suffix of  , or vice versa. In the former case, we can write

, or vice versa. In the former case, we can write  and

and  ; in the latter case,

; in the latter case,  and

and  .

.

Reduce the word  using

using  first, then using

first, then using  first. Call the results

first. Call the results  , respectively. If

, respectively. If  , then we have an instance where confluence could fail. Hence, add the reduction

, then we have an instance where confluence could fail. Hence, add the reduction  to

to  .

.

After adding a rule to  , remove any rules in

, remove any rules in  that might have reducible left sides.

that might have reducible left sides.

Repeat the procedure until all overlapping left sides have been checked.

Example

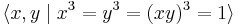

Consider the monoid:  . We use the shortlex order. This is an infinite monoid but nevertheless, the Knuth–Bendix algorithm is able to solve the word problem.

. We use the shortlex order. This is an infinite monoid but nevertheless, the Knuth–Bendix algorithm is able to solve the word problem.

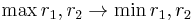

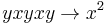

Our beginning three reductions are therefore (1)  , (2)

, (2)  , and (3)

, and (3)  .

.

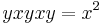

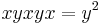

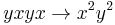

Consider the word  . Reducing using (1), we get

. Reducing using (1), we get  . Reducing using (3), we get

. Reducing using (3), we get  . Hence, we get

. Hence, we get  , giving the reduction rule (4)

, giving the reduction rule (4)  .

.

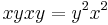

Similarly, using  and reducing using (2) and (3), we get

and reducing using (2) and (3), we get  . Hence the reduction (5)

. Hence the reduction (5)  .

.

Both of these rules obsolete (3), so we remove it.

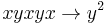

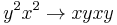

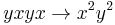

Next, consider  by overlapping (1) and (5). Reducing we get

by overlapping (1) and (5). Reducing we get  , so we add the rule (6)

, so we add the rule (6)  . Considering

. Considering  by overlapping (1) and (5), we get

by overlapping (1) and (5), we get  , so we add the rule (7)

, so we add the rule (7)  . These obsolete rules (4) and (5), so we remove them.

. These obsolete rules (4) and (5), so we remove them.

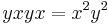

Now, we are left with the rewriting system

- (1)

- (2)

- (6)

- (7)

Checking the overlaps of these rules, we find no potential failures of confluence. Therefore, we have a confluent rewriting system, and the algorithm terminates successfully.

Generalizations

If Knuth–Bendix does not succeed, it will either run forever, or fail when it encounters an unorientable equation (i.e. an equation that it cannot turn into a rewrite rule). The enhanced completion without failure will not fail on unorientable equations and provides a semi-decision procedure for the word problem.

The notion of logged rewriting discussed in the paper by Heyworth and Wensley listed below allows some recording or logging of the rewriting process as it proceeds. This is useful for computing identities among relations for presentations of groups.

References

- D. Knuth and P. Bendix. "Simple word problems in universal algebras." Computational Problems in Abstract Algebra (Ed. J. Leech) pages 263–297, 1970.

- C. Sims. 'Computations with finitely presented groups.' Cambridge, 1994.

- Anne Heyworth and C.D. Wensley. "Logged rewriting and identities among relators." Groups St. Andrews 2001 in Oxford. Vol. I, 256–276, London Math. Soc. Lecture Note Ser., 304, Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge, 2003.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||